From December 11th, 2022 – April 15th, 2023 an exhibit showing the intense work Guilermo Del Toro and the team at ShadowMachine as well as Mackinnon & Saunders put into making the stop motion Pinocchio that can be seen on Netflix. Before the exhibit closed P-CS made sure to check it out and take as many intricate photos as positiong, crowd control and security allowed.

Following are those photos as well as photos of text printed on the wall of exhibit converted to easy reading in blockquotes. You can also still see MOMA’s exhibit page for more information.

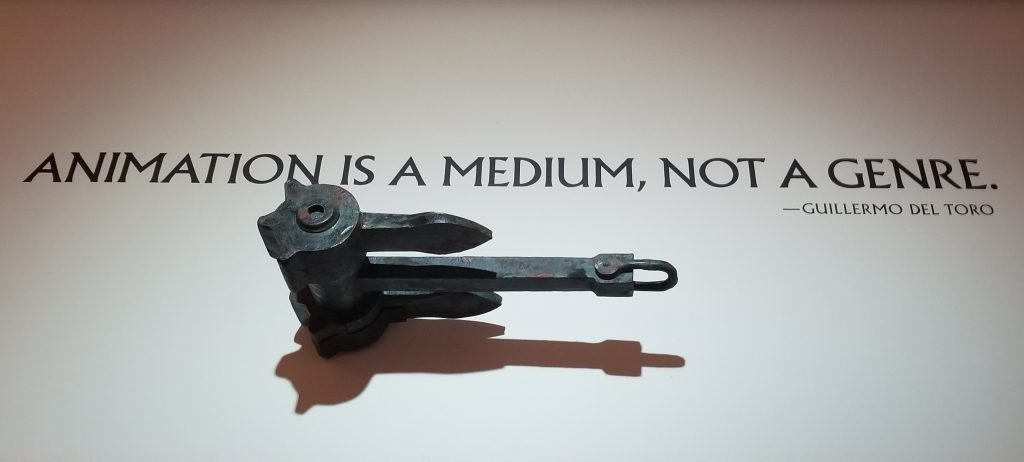

“No art form has influenced my life and my work more than animation, and no single character in history has had as deep of a personal connection to me as Pinocchio,” Guillermo del Toro has stated. For the film director, animation is not a genre reserved exclusively for the entertainment of children; it is a medium fully capable of engaging people of all ages. This belief has inspired his first work in stop-motion, a technique in which objects are positioned and photographed, then manipulated slightly and photographed again, over and over, to produce the appearance of movement.

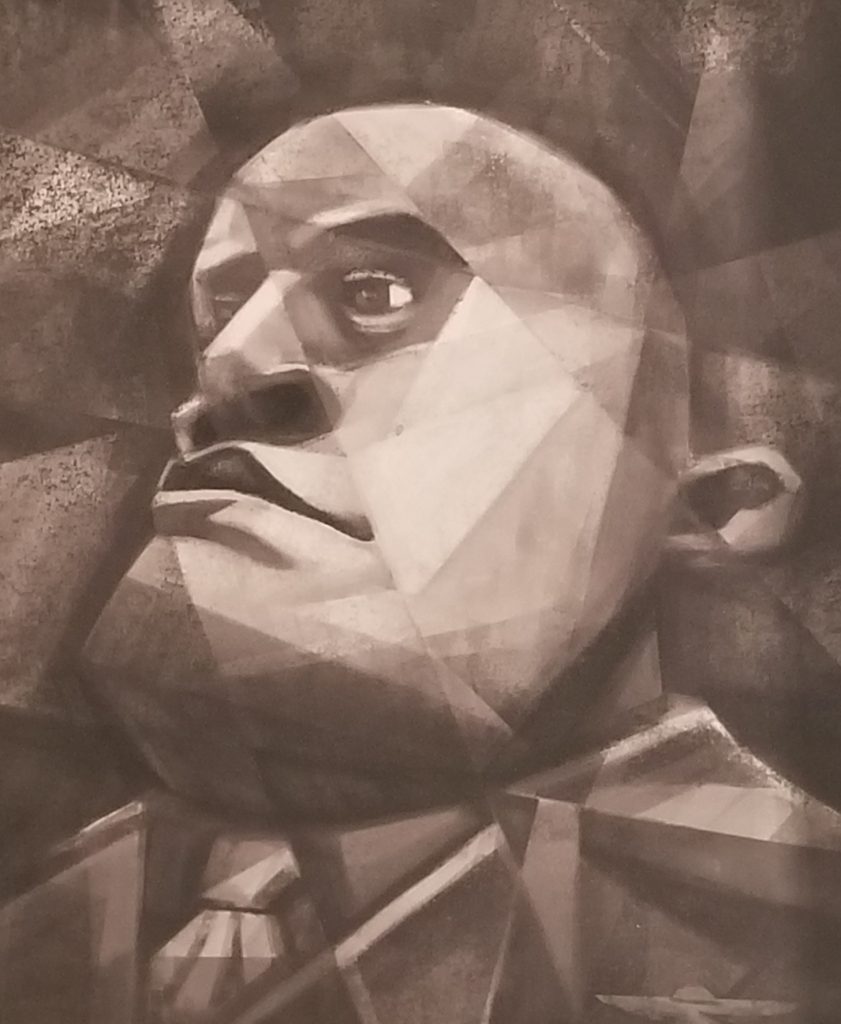

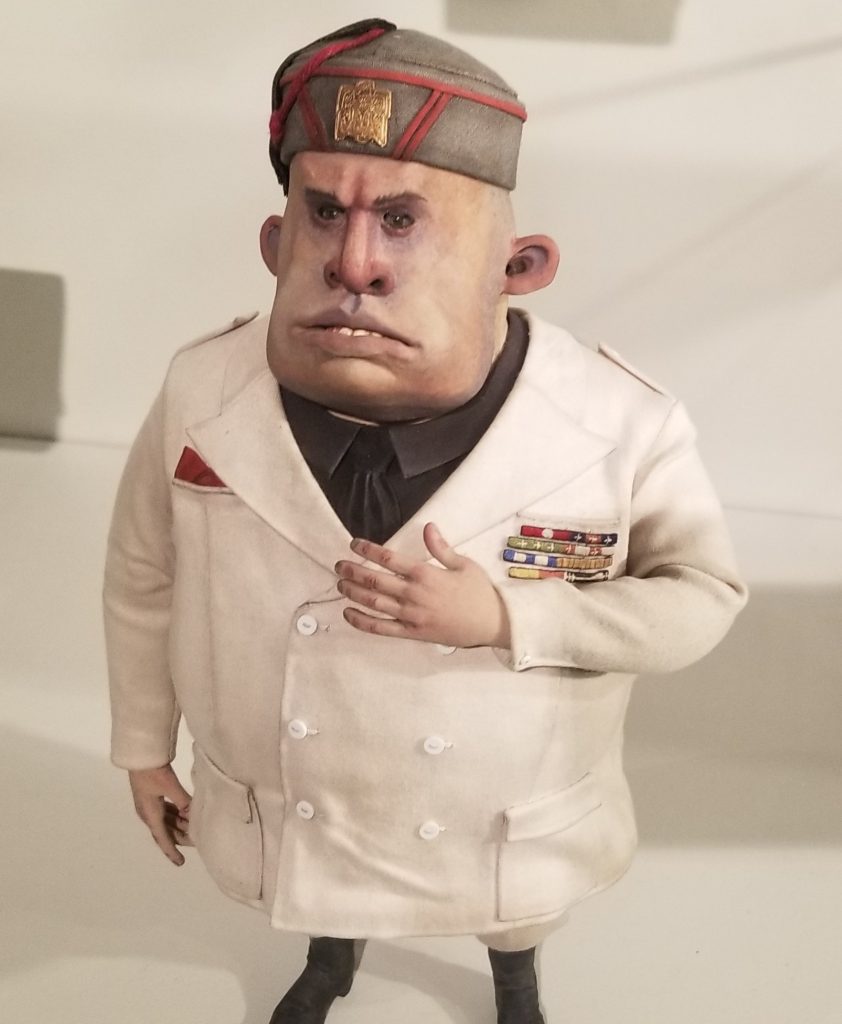

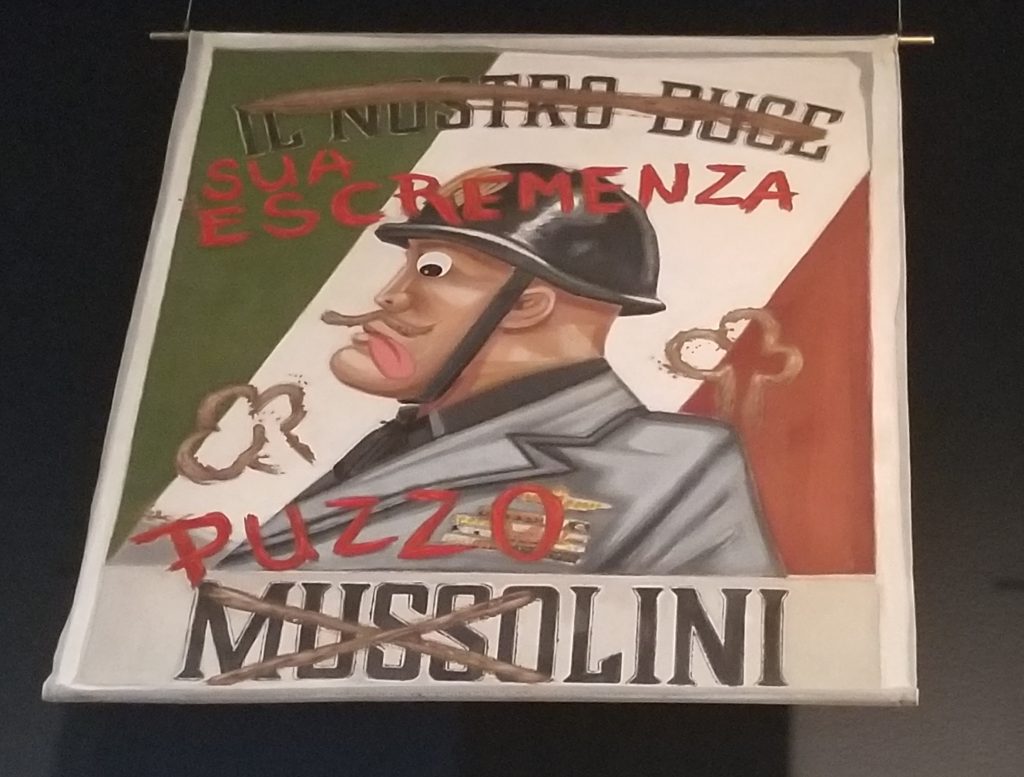

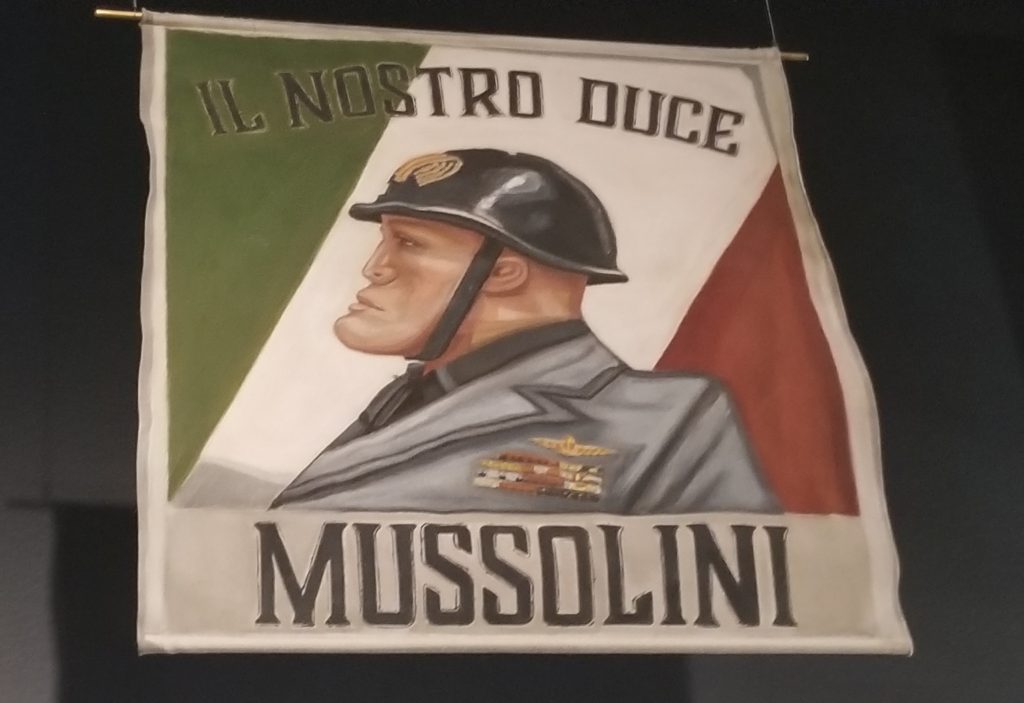

The Adventures of Pinocchio (1883), a folktale by the Italian writer Carlo Collodi, has been published in countless editions (242 in Italian alone), translated into more than 135 languages, and illustrated repeatedly for generations of readers and moviegoers. Setting his adaptation in Fascist-era Italy, del Toro connects this classic story about a wooden boy in the adult world with themes central to all his work: youth and maturity, authority and disobedience, aloneness and spirituality.

Organized while the film was being made in Portland, Oregon, Guadalajara, Mexico, and Altrincham, England, this exhibition focuses on the crafts employed in the process of bringing del Toro’s vision to the screen. Materials from the “look development” phase reveal the diverse approaches and mediums used in fabricating the handmade physical world of the film, the historical research grounding it in reality, and the different forms the puppet characters took before they appeared before the camera. Large-scale working sets from the film’s production offer a behind-the-scenes experience. Supporting documentation-time-lapse, motion study, and animation software videos-demonstrates the coordinated efforts that empower the art of stop-motion to be as expressive and resonant as live performance.

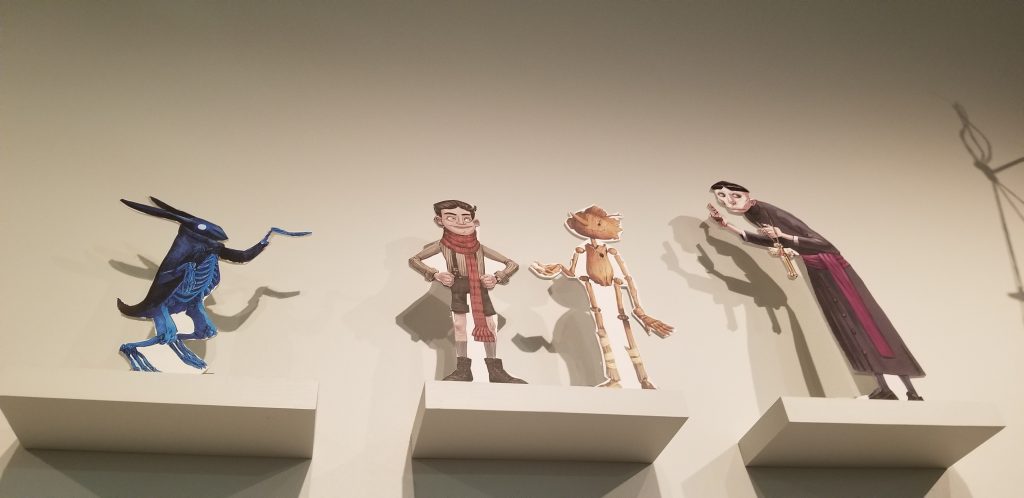

LOOK DEVELOPMENT

Look development is a creative process that occurs before shooting begins on a film. Artists and craftspeople spend many months experimenting with the different mediums and methods required to visualize what is described in the script, storyboard, and concept art. Bringing Guillermo del Toro’s unique adaptation of the Pinocchio tale to life on screen involved a significant amount of research and testing.

On view here are examples of the film’s look-development teams’ explorations of the natural elements that compose Pinocchio’s world, including wood, stone, metal, foliage, and light; the historical period in which the story is set; and the different ways the human and supernatural characters would appear and move. Often crafted using unconventional or recycled materials, these crucial exercises aided the crew in developing a cohesive design. As the film went into production, materials like these were kept on display in the studio to help the project’s many collaborators-designers, puppet makers, and animators-maintain a consistent vision.

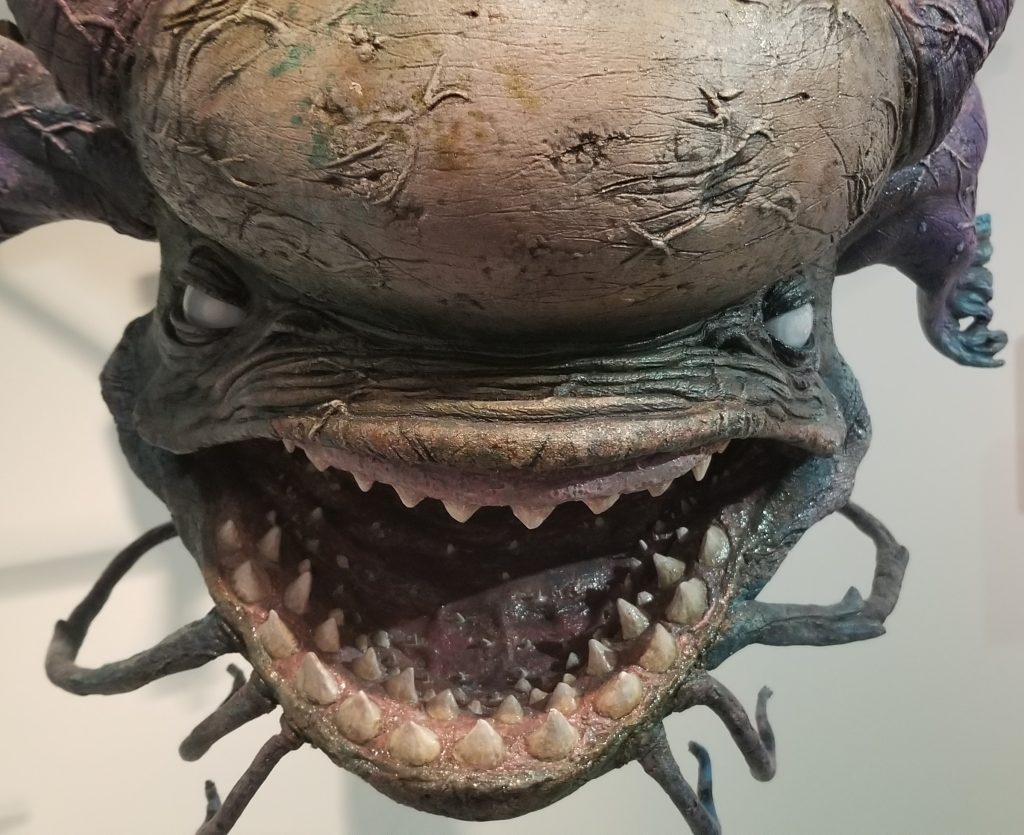

Pinocchio encounters the Dogfish, a sea- dwelling beast, on his quest to discover what it means to be alive. With the goal of grounding the design of the fantastical Dogfish in nature, some of the first look-development experiments for this character involved everyday foods. Silicone and resin castings of tomatoes, kale, and other vegetables-which showed their texture, color, and veining-provided inspiration for the Dogfish’s skin, texture, and scarring. Lead look-development artist Caitlin Pashalek recalls “stealing from nature as opposed to ‘making a sculpted thing.’… I tried to find materials and processes that could be slightly uncontrolled, that had interest and a life of their own.”

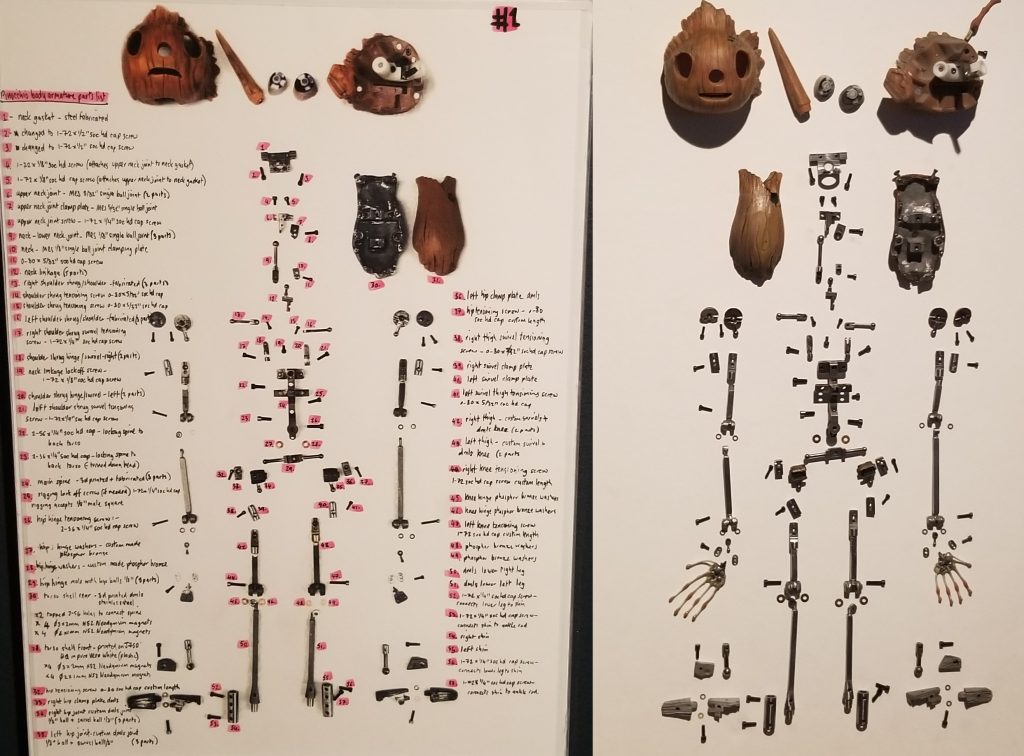

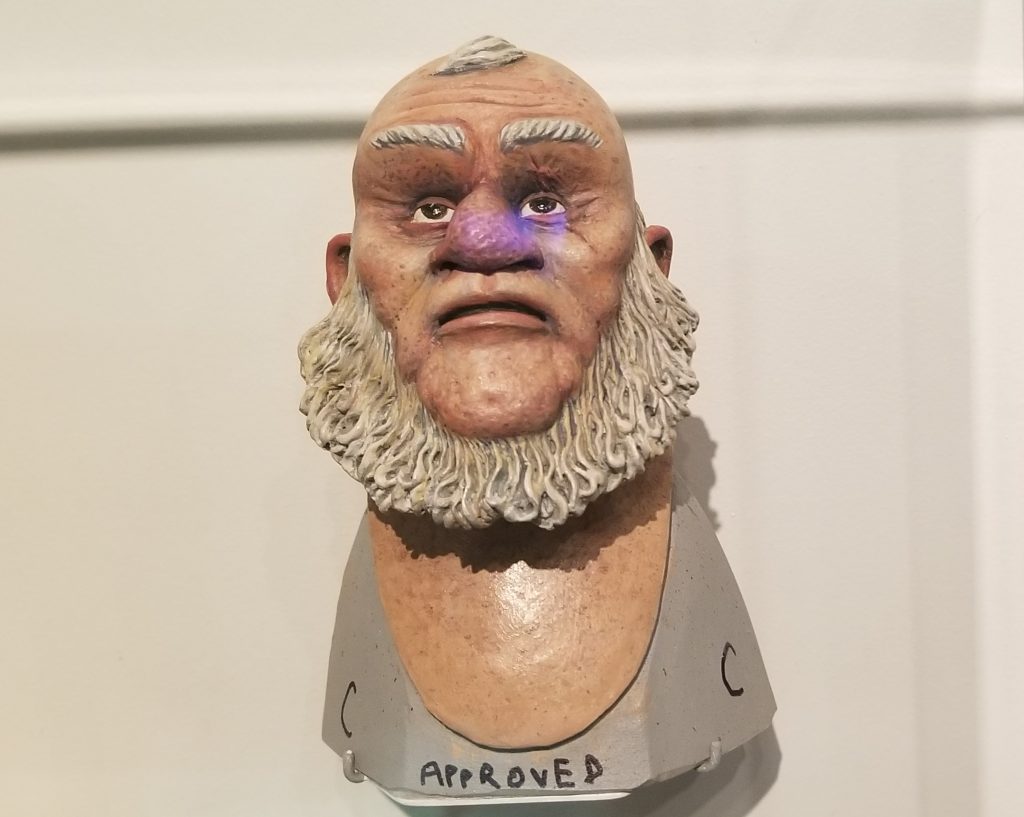

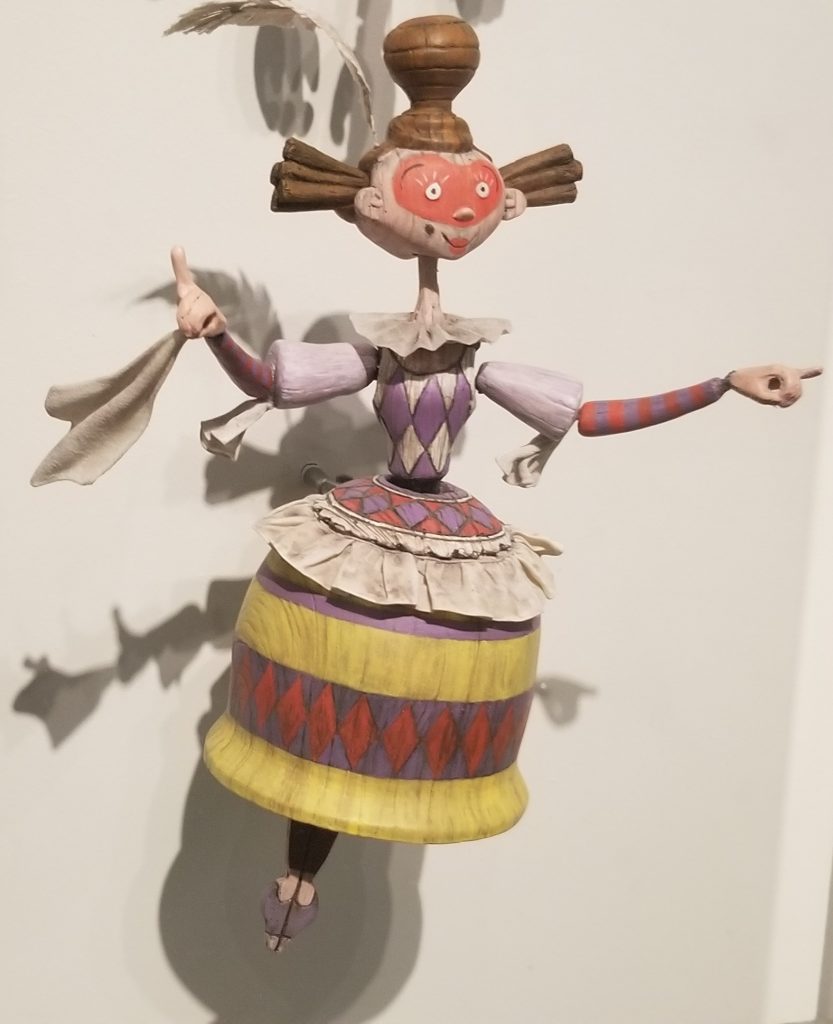

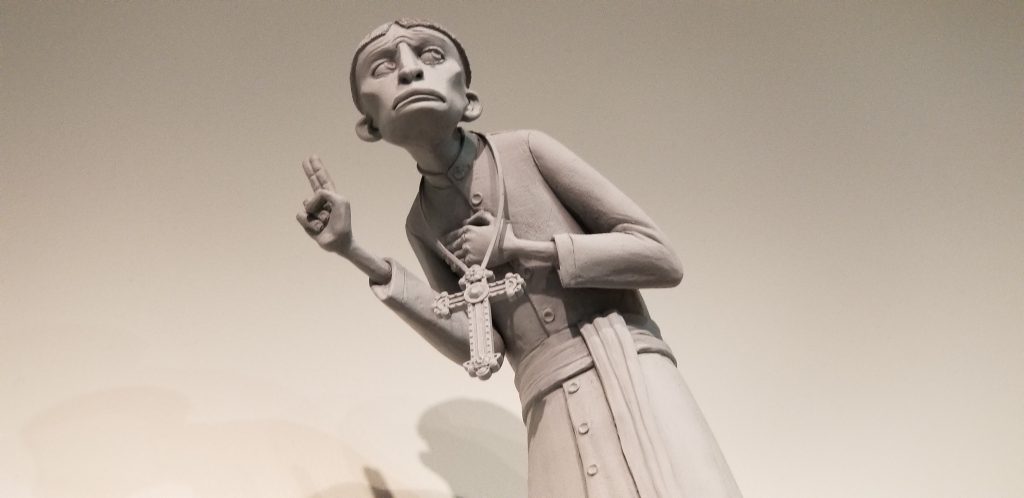

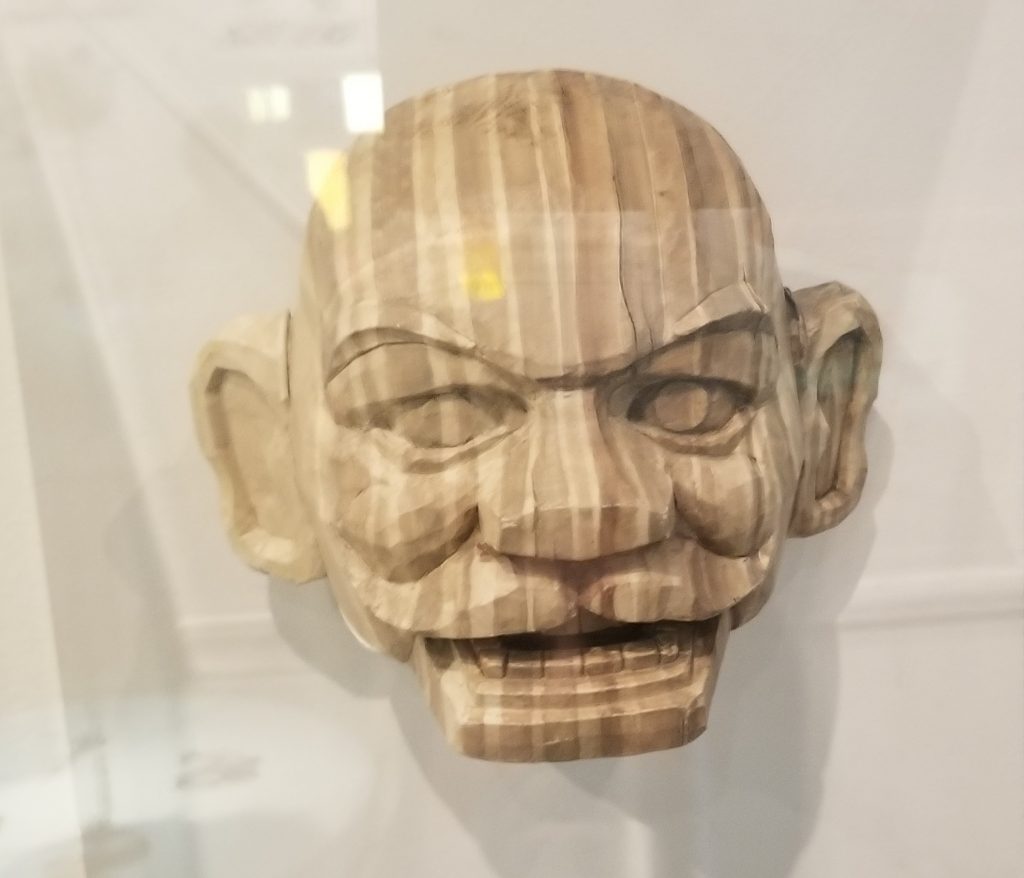

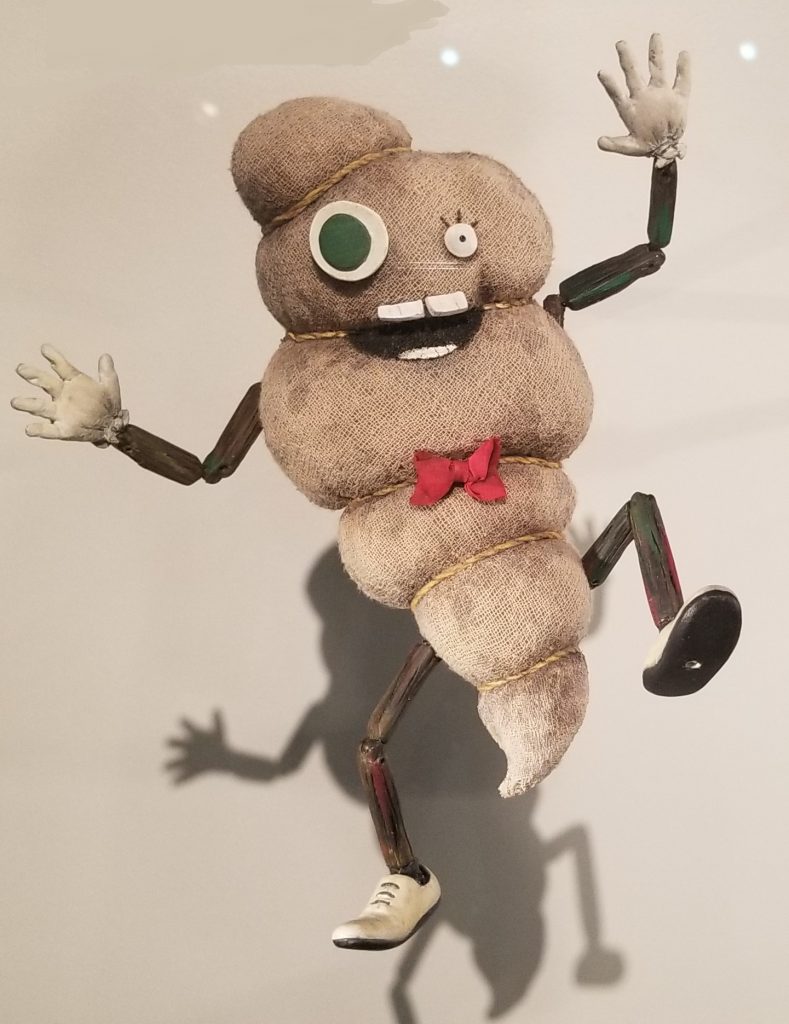

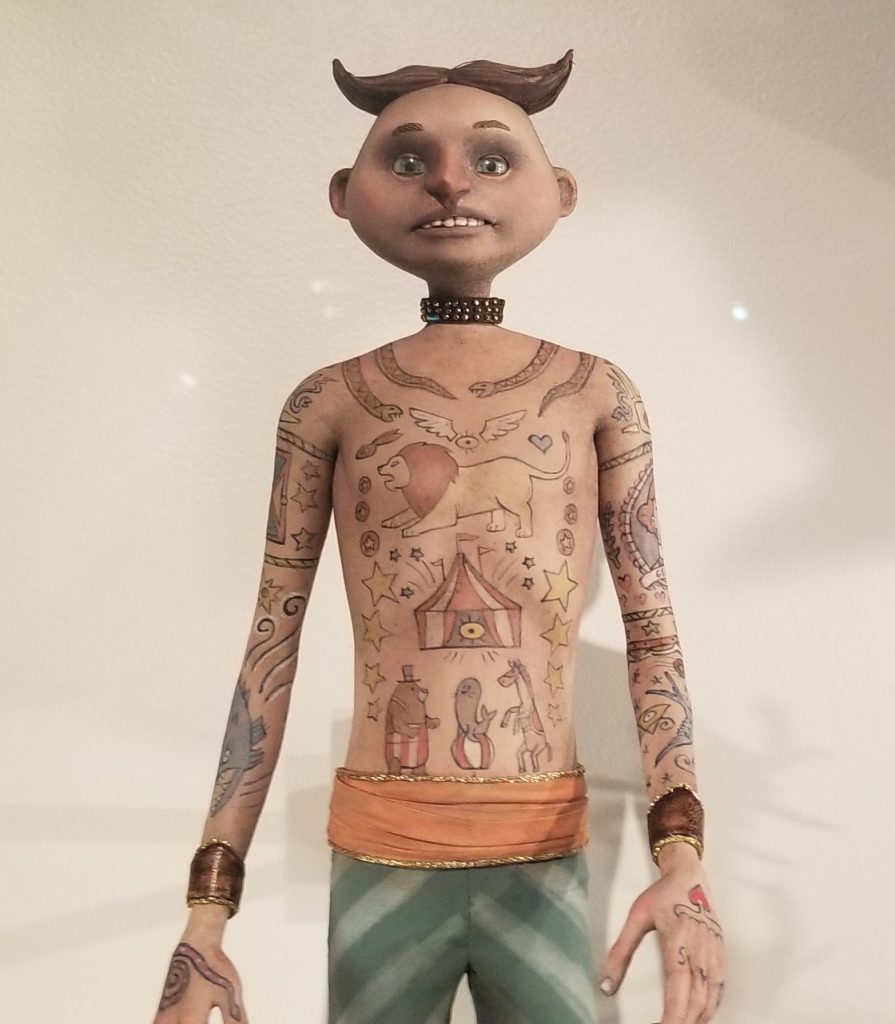

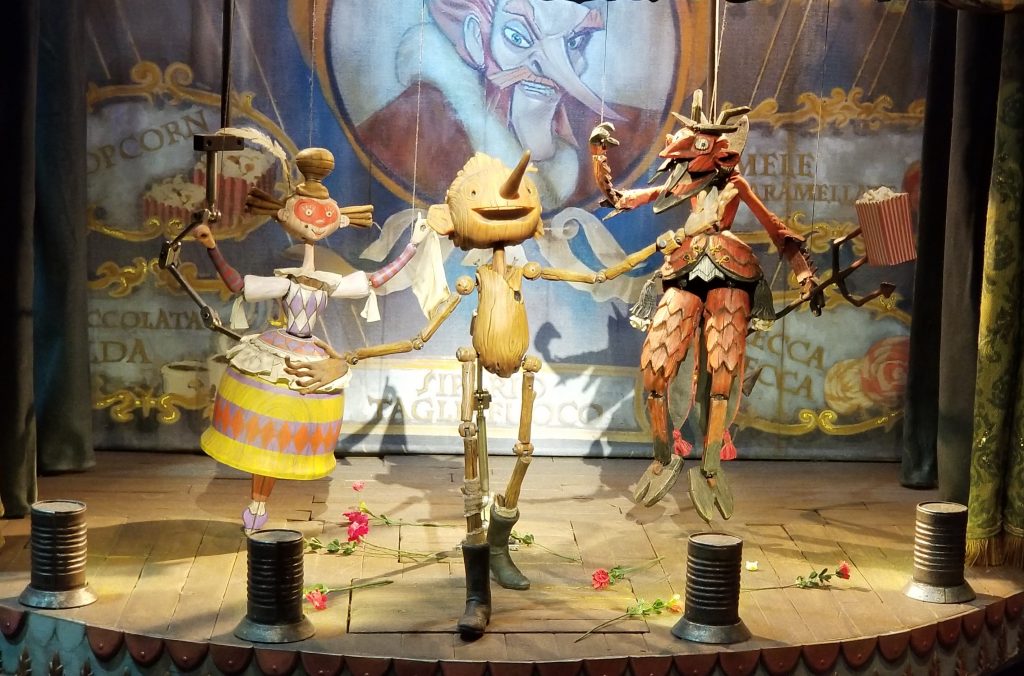

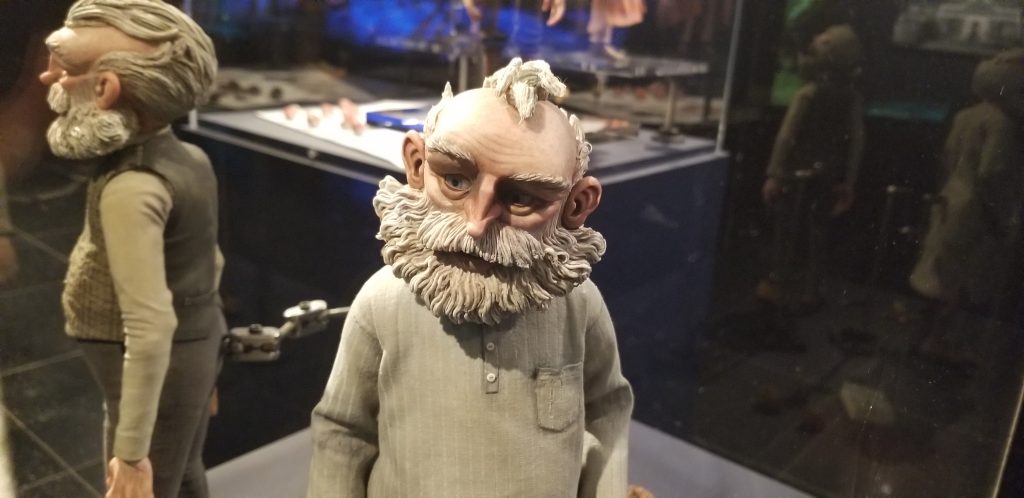

PUPPETS

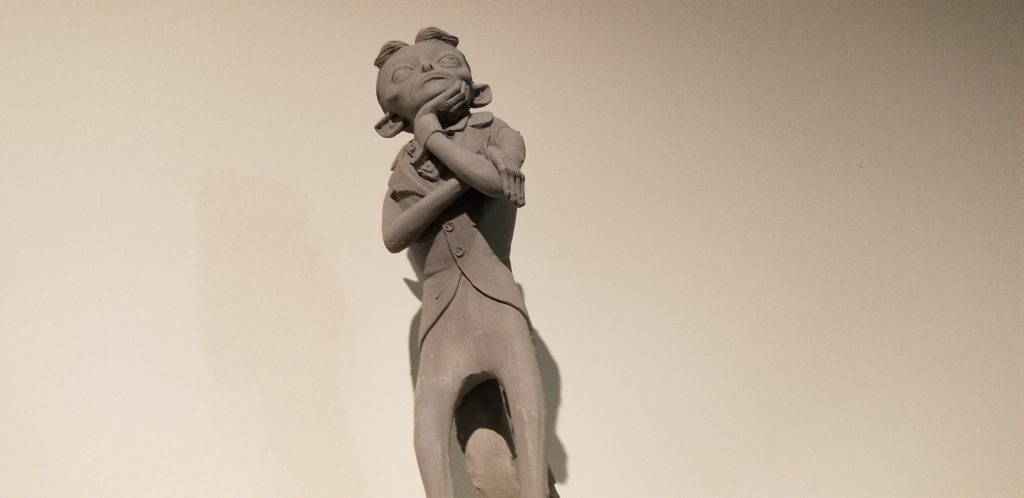

A puppet begins with a design. After its shape, features, and scale are explored, a maquette (a preliminary model) is crafted, which allows a film’s creative team to see the design in three dimensions and at full scale, and to make adjustments accordingly. From there, the technical elements are developed. For example, armature specialists engineer the mechanical insides of the puppet-a complex system of miniature gears, wires, and paddles-enabling an animator to move it. Finally, the armature is padded with foam, finished with silicone, painted, and costumed. “We wanted the sets and the characters to feel beautiful, sculpted, and old-world,” Guillermo del Toro explained. “This is a movie that emphasizes the fact that it’s handmade.”

Organized by medium, the puppets here include examples from many stages of the process: finished hero puppets, clay sculptures, molds, miniatures, foam-core stand-ins, and more.

Wood is the most prominent material in Pinocchio, and all the wooden elements-from Geppetto’s carpentry workshop to the town church to Pinocchio himself-needed to work together from a visual and narrative perspective. Therefore, the exploration of the tone, texture, and overall feel of wood was a key aspect of look development. As art director Rob DeSue recalls, “We worked with noncompetitive colors and values and also used diminished details for grain and relief. That way, in an environment composed of earth tones, stone, and wood, Pinocchio was always the most special object in the frame.”

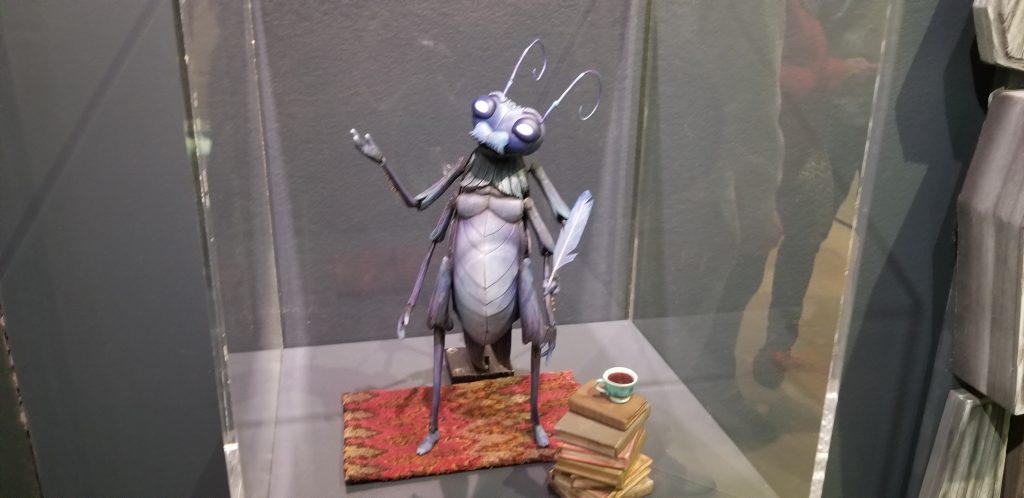

Reflecting the notion that there is no life without death-one of the most significant themes of del Toro’s Pinocchio-the two are embodied as inseparable sisters, named Wood Sprite and Death, who guide Pinocchio to the afterlife, called Limbo. The doors to Limbo were crafted in gray to allow precise on-set lighting in carefully selected shades of blue. “The Dogfish, Death, the Sprite, the Cricket, and the rabbits all have the same sort of unworldly blue-violet skin, because they are all related,” del Toro explained. “The rabbits are an extension of death, which is the sister of life. And they wear identical masks.”

Village corner set 2020

Mixed media, puppets, and steel rigging

Courtesy Netflix Physical Assets & Archives

This is a small portion of one of the largest sets built for the film. In the story, the rise of fascism causes this village to go through many subtle physical changes. While nearly everything seen in the finished film is tangible and handcrafted, green screens were used to place artificial backgrounds and enabled multiple scales of puppets to appear in a single frame. Here, the green screen is used to digitally place a hand- painted image of the sky.

Geppeto’s Workshop

At the center of Geppetto’s village is a church that was built over centuries by residents using different materials and woodworking techniques, and which shows both modern and medieval influences. The wooden sculpture of Christ, which resembles Pinocchio, was carved by Geppetto himself. The stained-glass windows and frescoes visually refer to other parts of Pinocchio’s story as well as to del Toro’s other films, in particular their themes of war, innocence, and monsters. Multiple versions of this meticulously crafted set, a portion of which is on view here, were created to allow multiple animation units to film simultaneously.

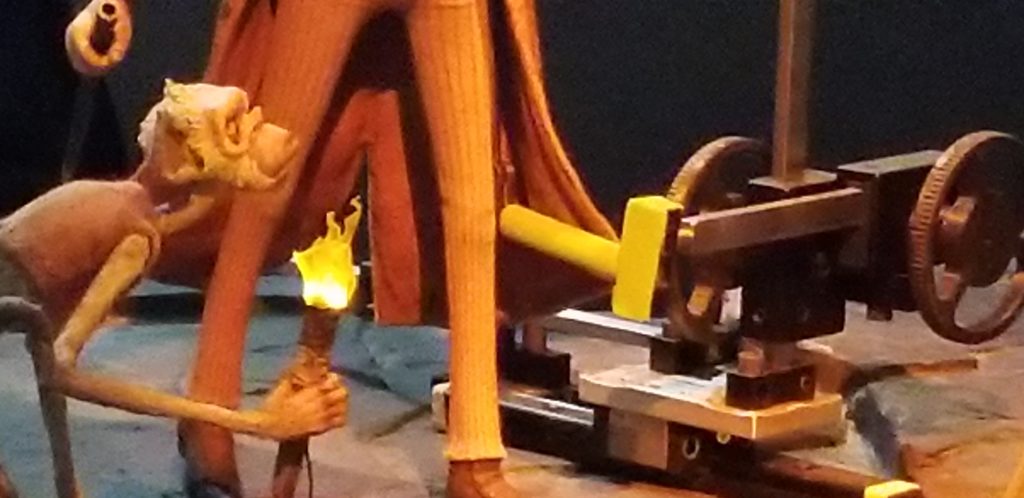

Re-education camp ocean cliff ledge set 2021

Mixed media, puppets, and steel rigging Courtesy Netflix Physical Assets & Archives

Most of the time, light sources that appear on screen only give the appearance of lighting the scene; offscreen lights do most of the actual lighting. However, in this pivotal scene, set on a cliffside just outside the Fascist re-education camp, director of photography Frank Passingham was able to make the most of lighting effects created in real time in front of the camera and then combined digitally in postproduction. Functioning as more than props, the bonfire and the torch were used to illuminate the characters. Careful attention was also paid to the scene’s wash of moonlight. In their intensity, the fire and the sky underscore the drama of the impending liberation of Spazzatura and Pinocchio.

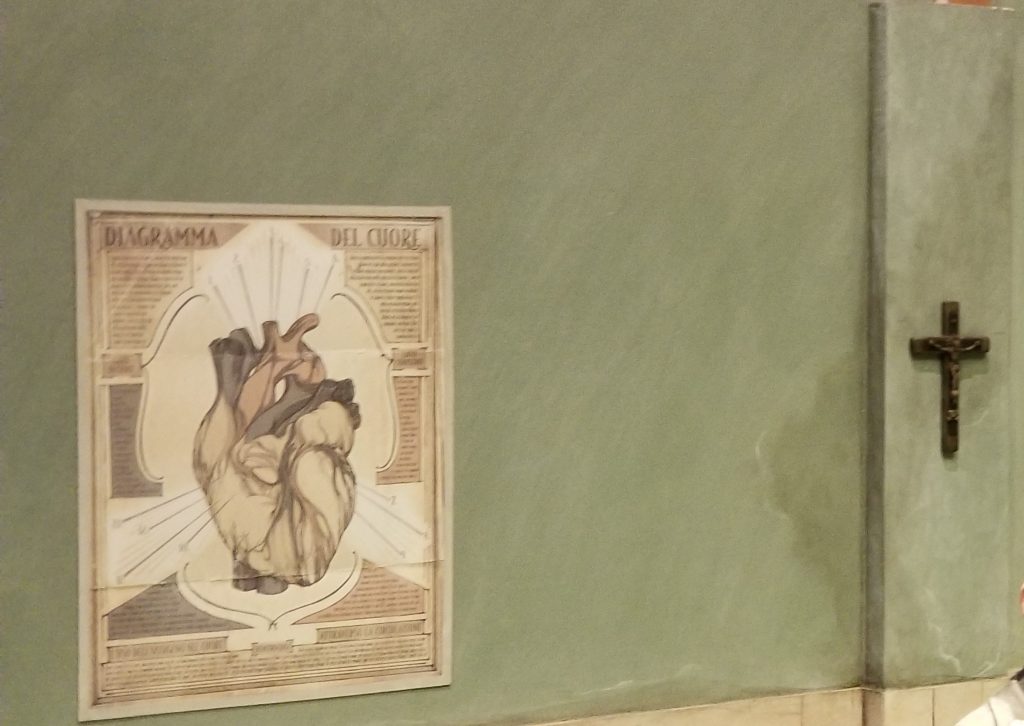

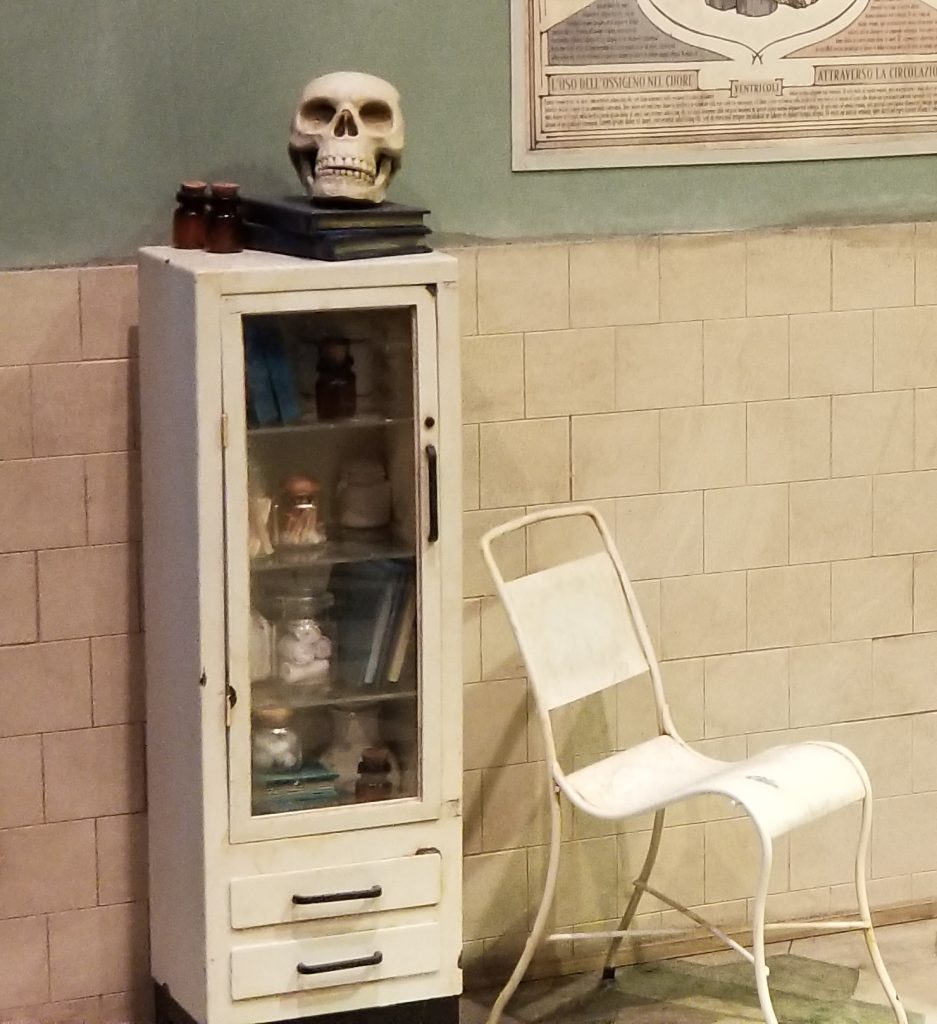

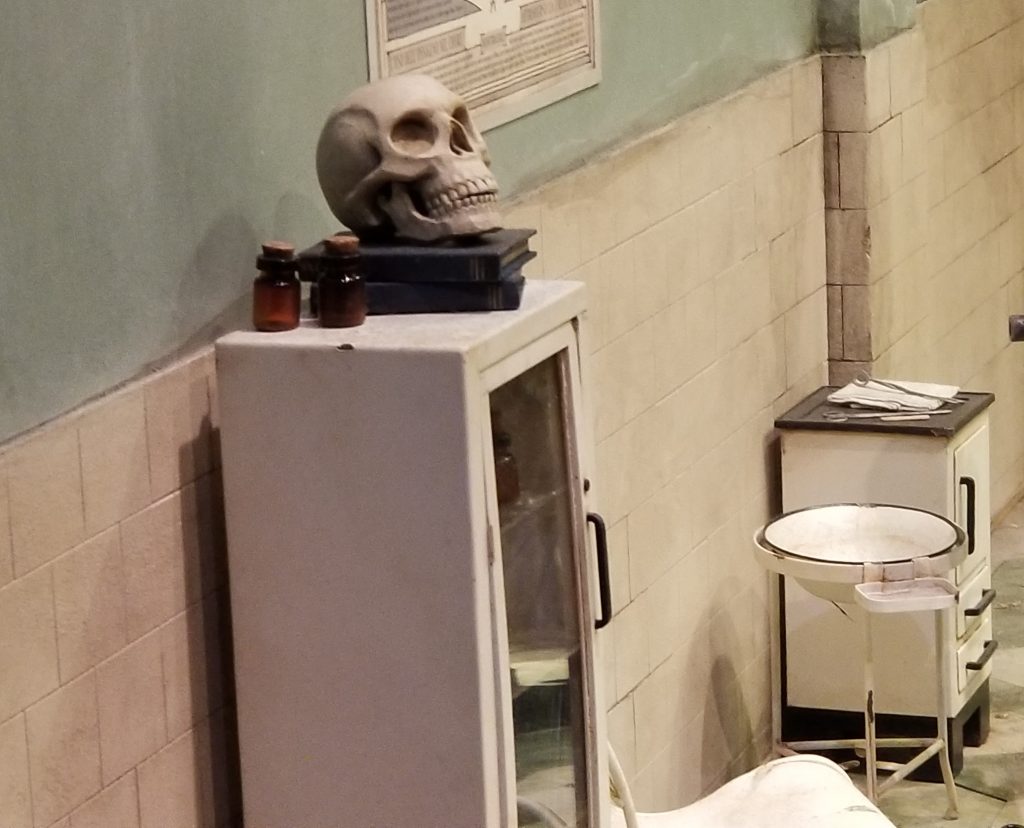

Doctor’s house set

Del Toro has always been interested in Frankenstein. “Pinocchio and Frankenstein have similar strands,” he explained. “Both are about an innocent, a pure force, created and abandoned in the world, and learning to cope morally with the world. He’s not a normal character, so he’s viewed with suspicion, with wonderment. He’s imprisoned, tortured.” Here, Pinocchio lies lifeless on an exam table, bringing to mind Frankenstein’s creation. Like Frankenstein, Geppetto made his creation by hand, which resulted in some imperfections: Pinocchio’s knees are different heights, one hand is more finished and one is more tree-like, and a branch springs from his head.

Reflecting on the decision to set the story in Mussolini-era Italy, del Toro said, “I thought Pinocchio could be a great opportunity to talk about disobedience. Obedience isn’t a virtue; it’s a burden. Disobedience is the seed of reason- it’s a desirable way to gain your own soul.” To emphasize this point, del Toro traded the Land of Toys in Carlo Collodi’s original Adventures of Pinocchio-where children are lured with the promise of freedom from school but ultimately turned into donkeys as punishment for their bad behavior-for a children’s Fascist re-education camp. Director of photography Frank Passingham and his camera team employed technology known as motion control to be able to move the camera in sync with the characters during this complex training sequence.

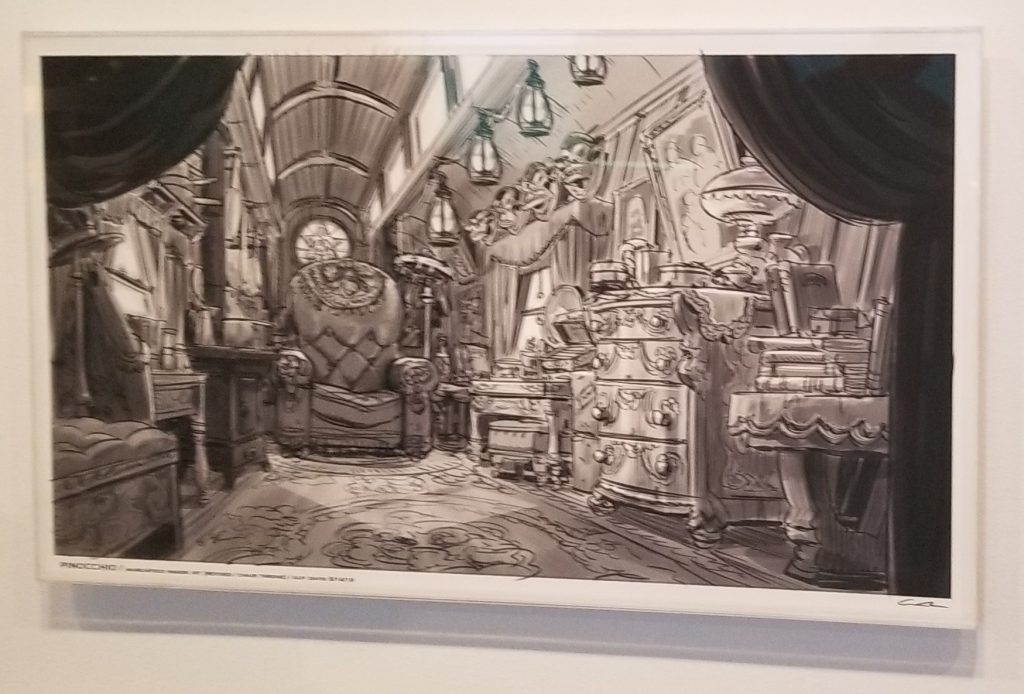

Volpe’s living wagon set 2019

Brass, steel, plywood, MDF, polyurethane resin, polyurethane foam, aluminum wire, polystyrene, PETG, and epoxy

Courtesy Netflix Physical Assets & Archives

Few scenes in Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio take place inside Volpe’s wagon, which serves as his home, but the vehicle offers a world of backstory if you look closely. The space is full of props like reused tea bags, the taxidermied ancestors of Spazzatura, who also lives in the wagon, and luxurious textiles that speak to Volpe’s former wealth. Around fifteen thousand props were made by hand for this film, each imbued with purpose and meaning.

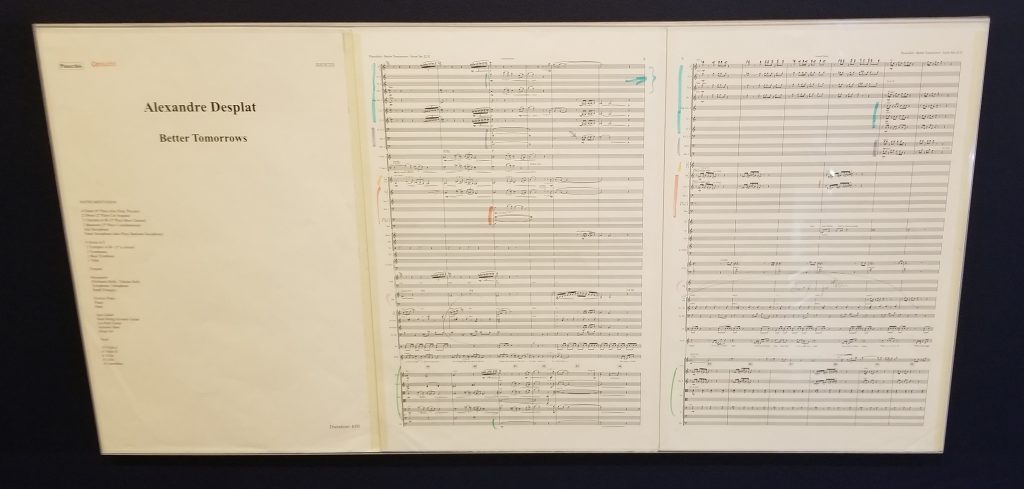

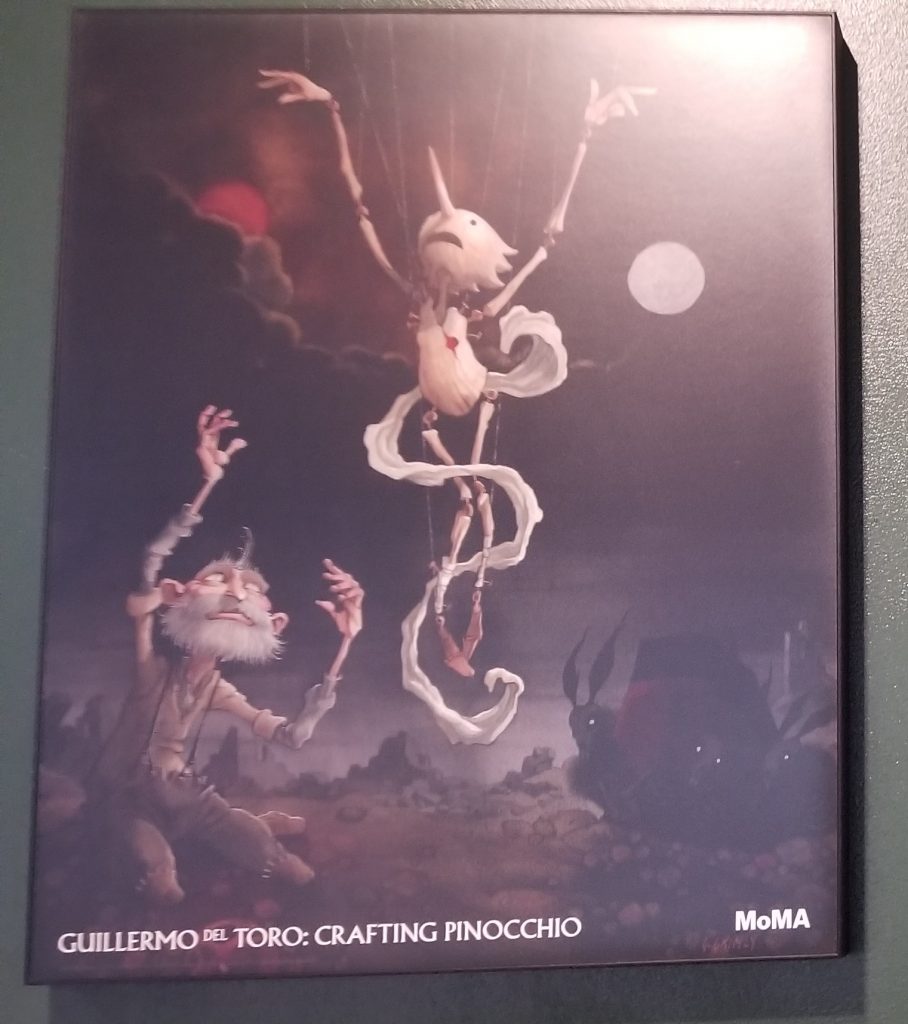

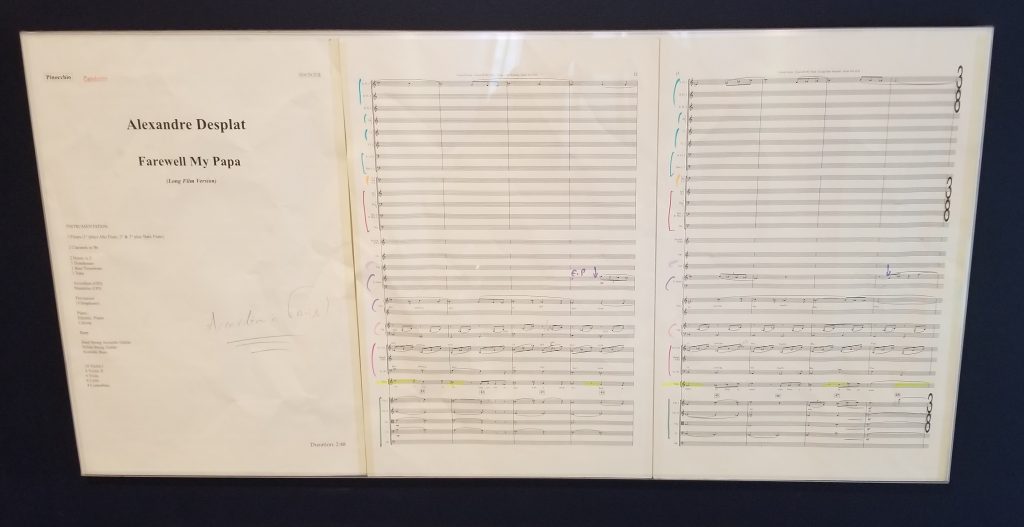

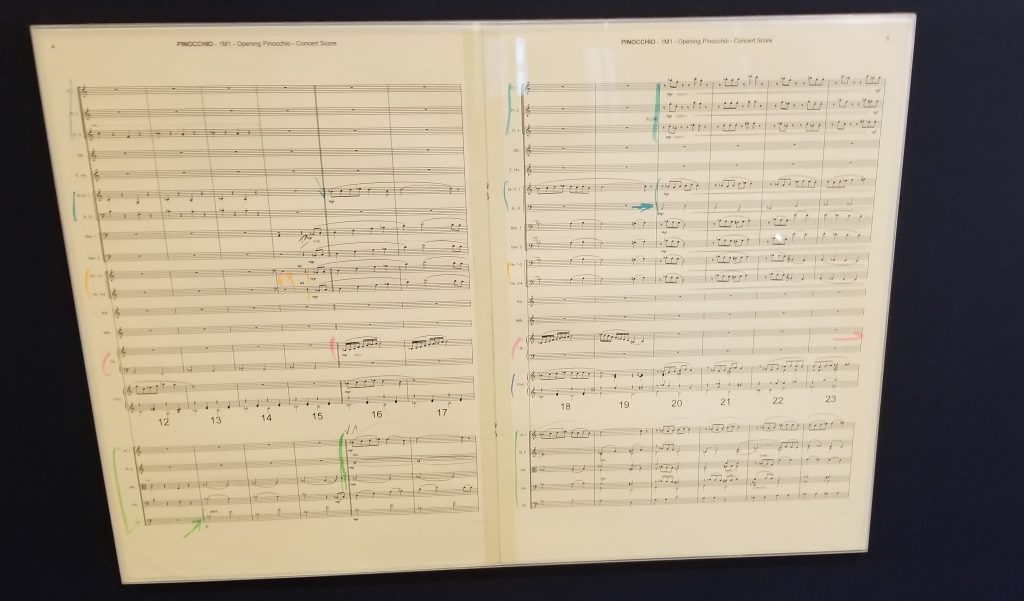

The Pinocchio exhibit actually took up two sections of MOMA. The main Crafting exhibit and then an exhibit on all of Guilermo Del Toro including documents and images that did not fit within the crafting section such sheet music, an exploration of Pinocchio history and large print posters of graphics from special edition blu-rays.

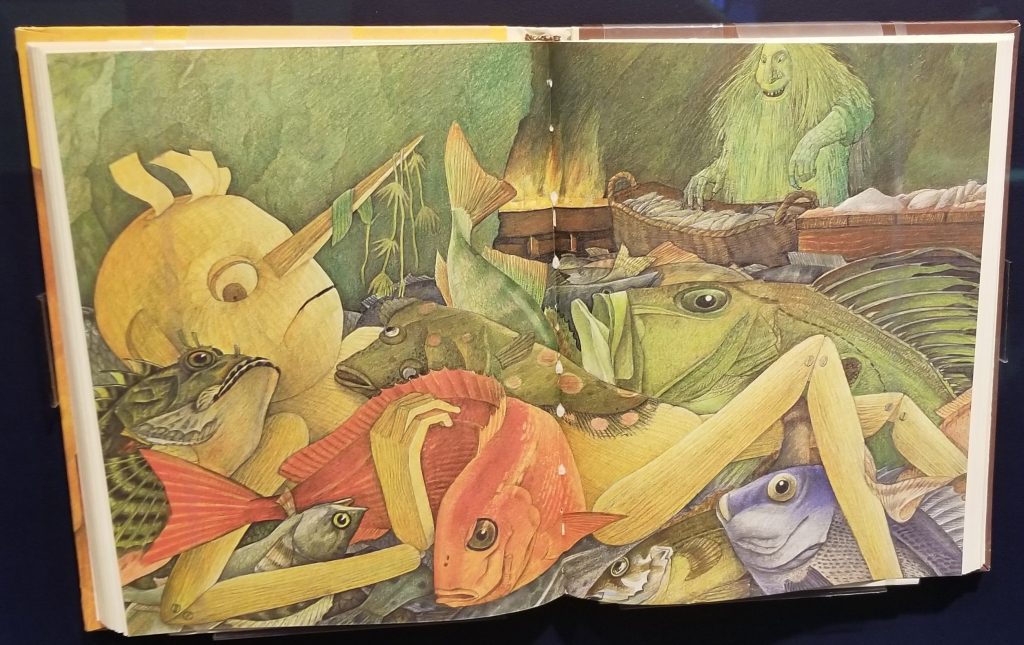

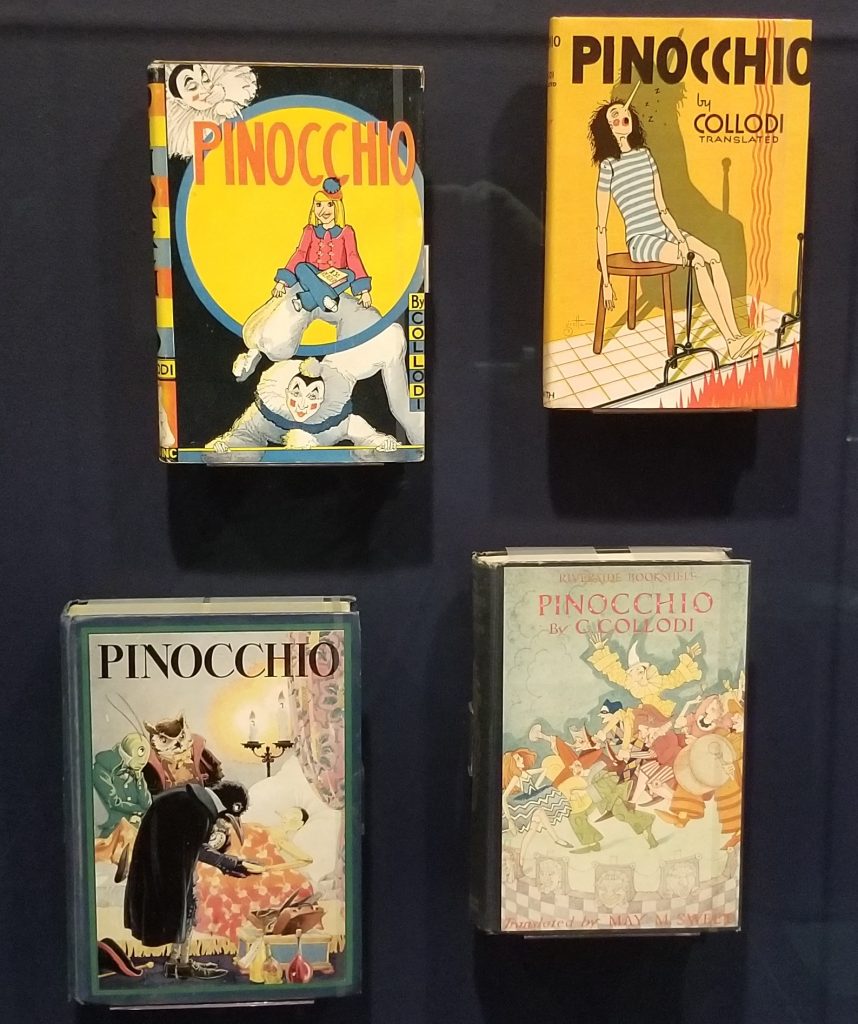

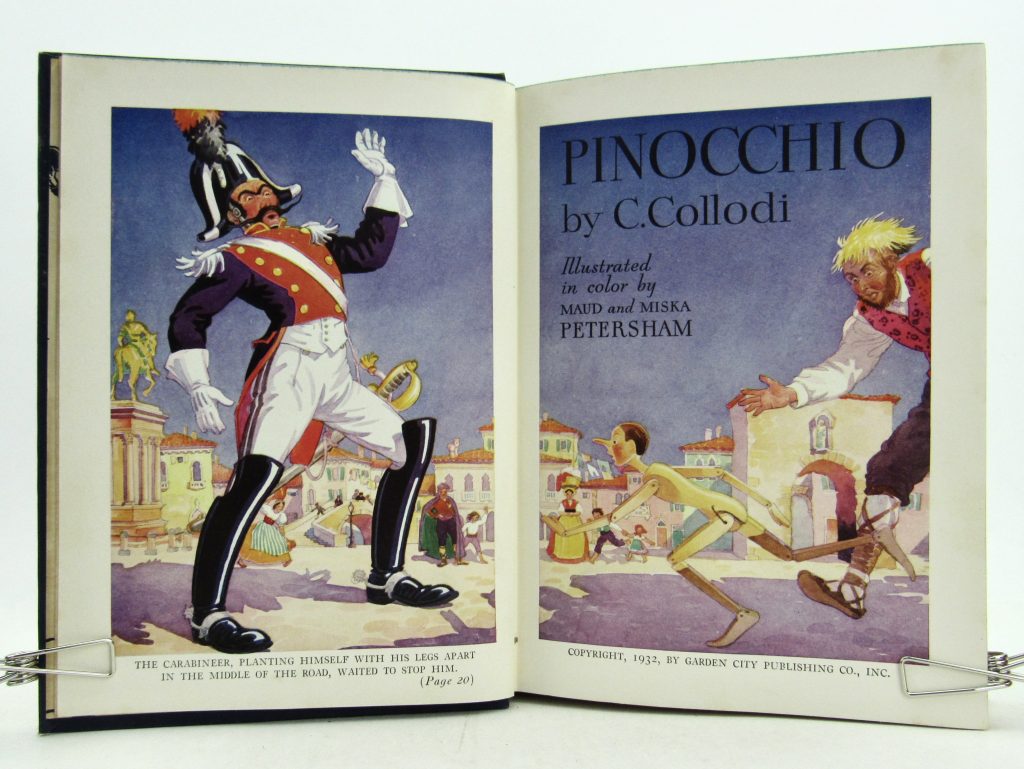

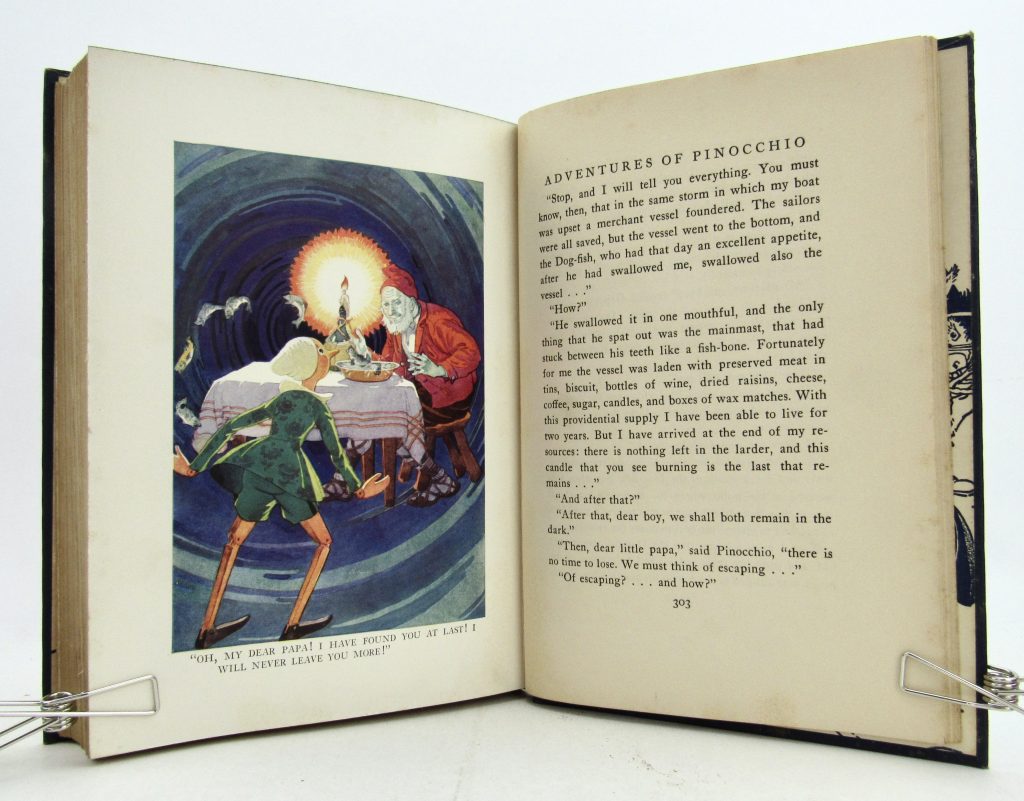

Since the first edition of Carlo Collodi’s Adventures of Pinocchio was published in Italy in 1883, with illustrations by Enrico Mazzanti, many artists around the world have visualized the book’s characters and situations. Among the notable cover illustrators represented here are Louise Beaujon, Carlos Bribián Luna, Jim Dine, Sara Fanelli, Richard Floethe, Joseph Clemens Gretter (Gretta), Dusty Higgins, Jaröna llo, Richard Kivit, Vincent Paronnaud (Winshluss), Maud Petersham, Tim Rollins, and Tony Sarg. These editions from China, Estonia, France, Israel, Italy, Russia, Spain, and the United States testify to the universality of Collodi’s folktale.

Alongside these covers P-CS also scoured the internet for interior imagery where possible.

Jaröna llo

L to R (clockwise): Jim Dine (2006 edition), Winshluss (2020 edition of 2008 GN), Richard Floethe (1937), Carlos Bribian Luna (2010)

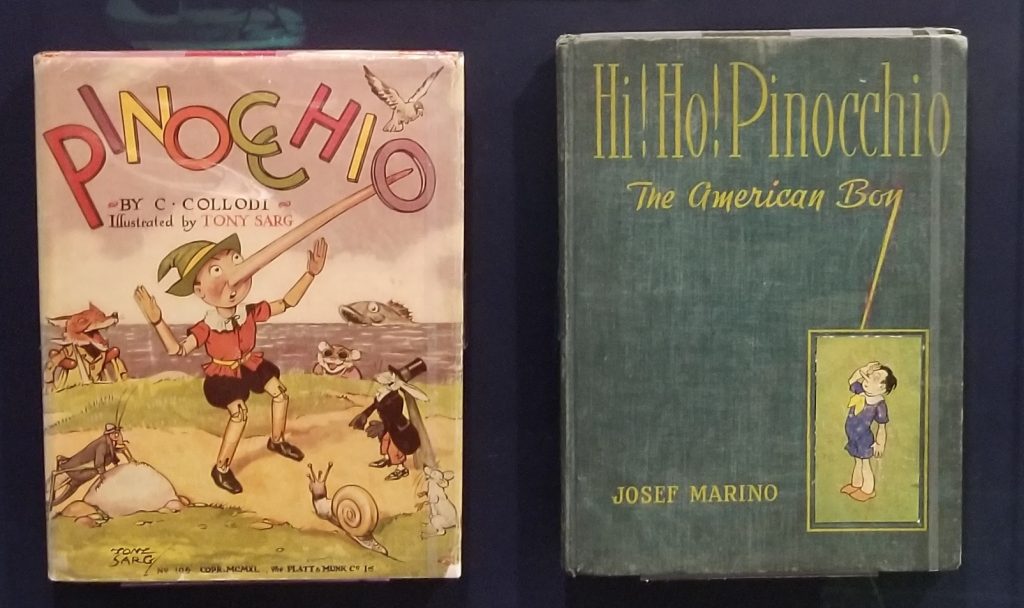

L to R: Tony Sarg (1940), Josef Marino (1940)

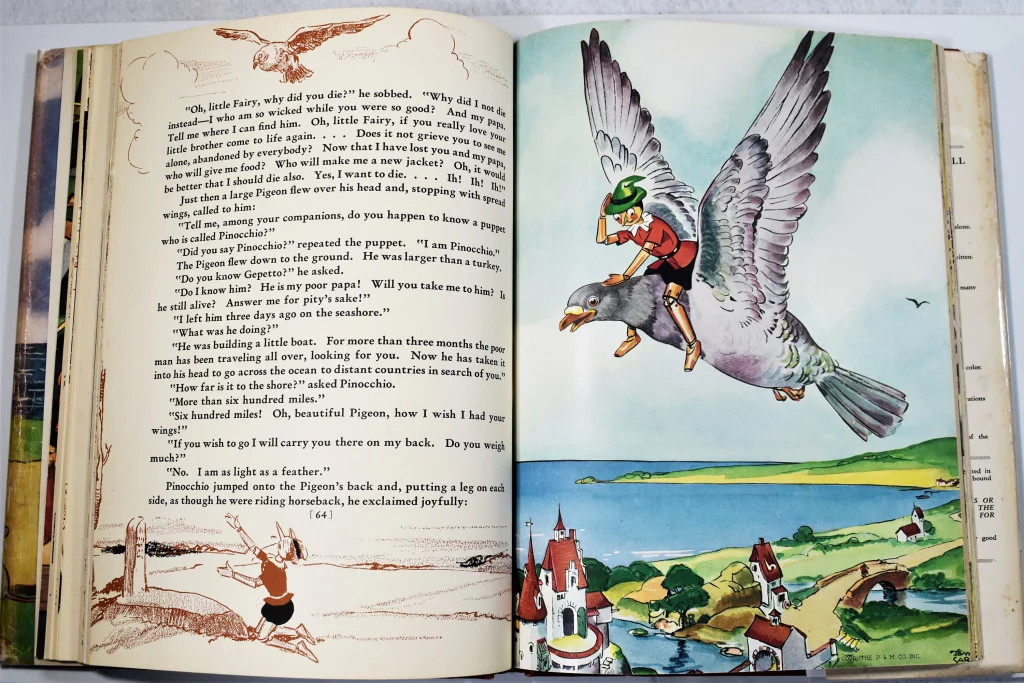

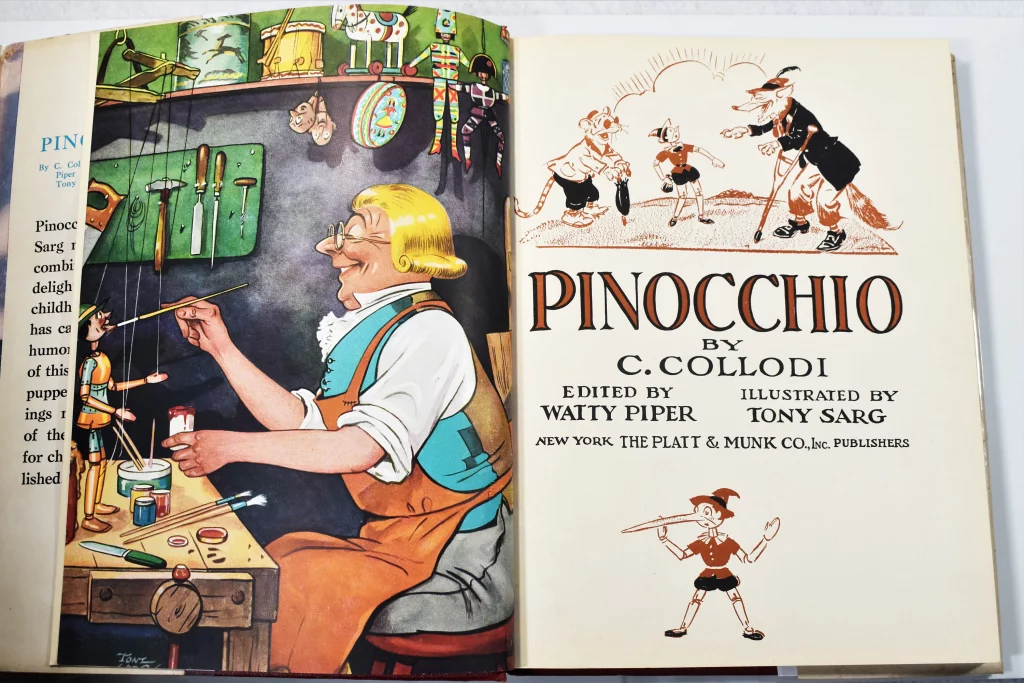

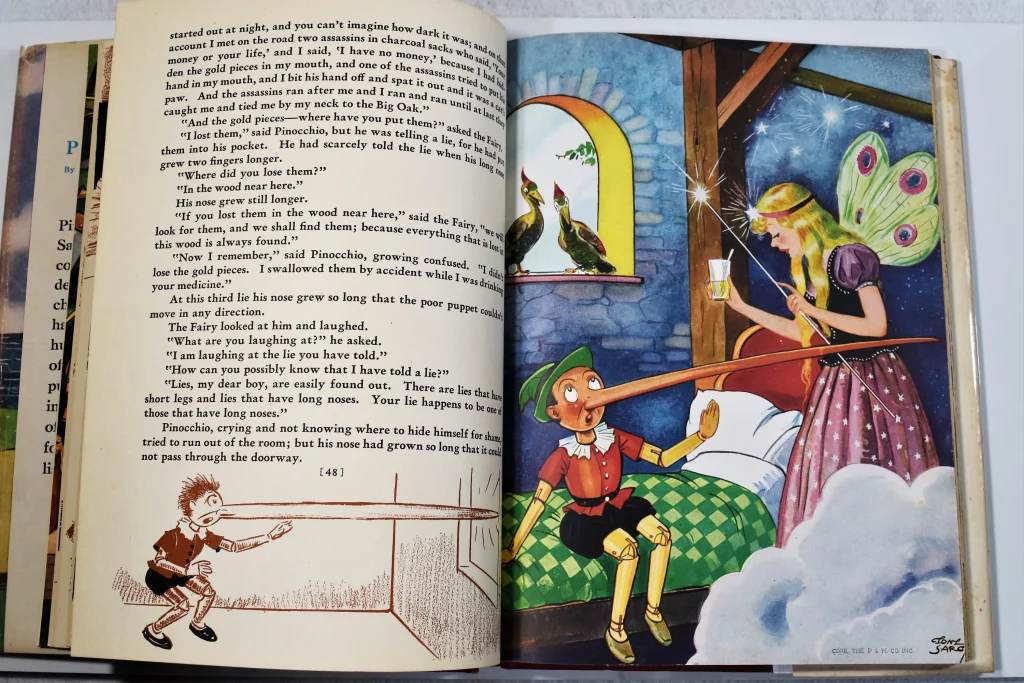

Here are some images from Tony Sarg’s book:

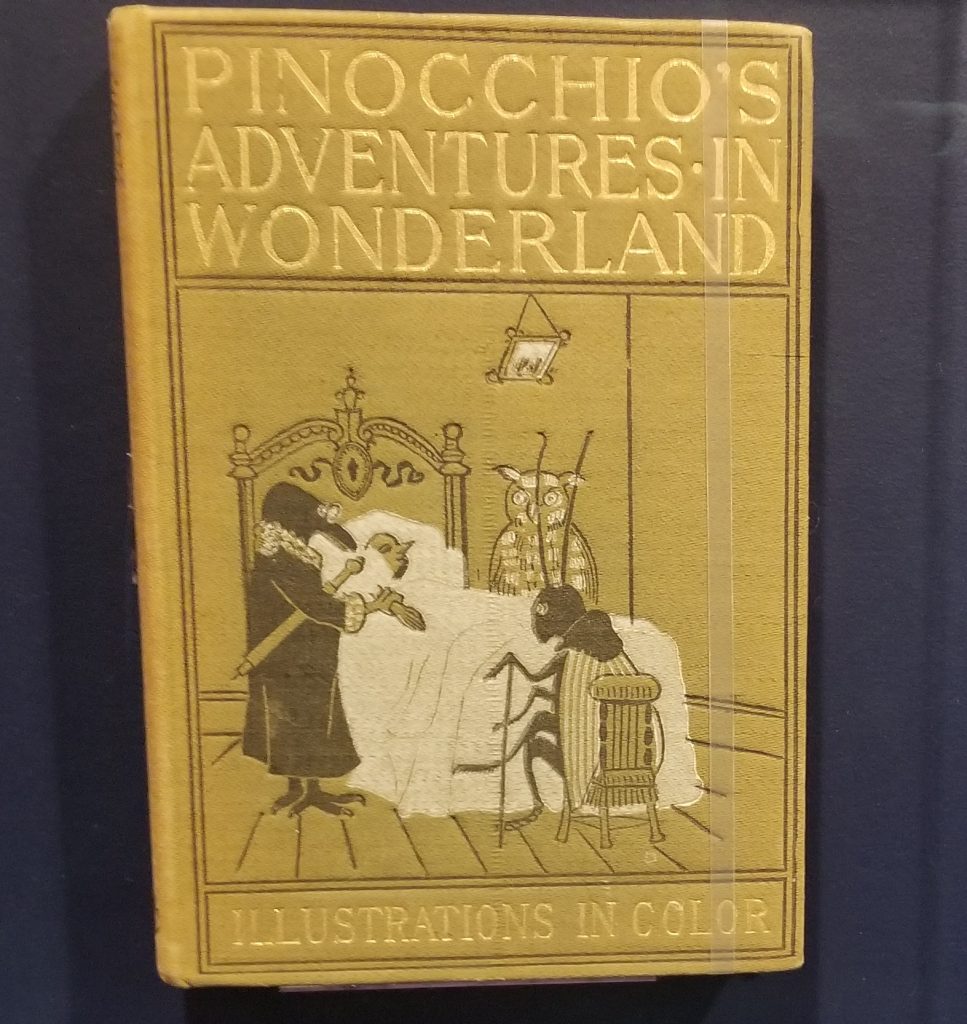

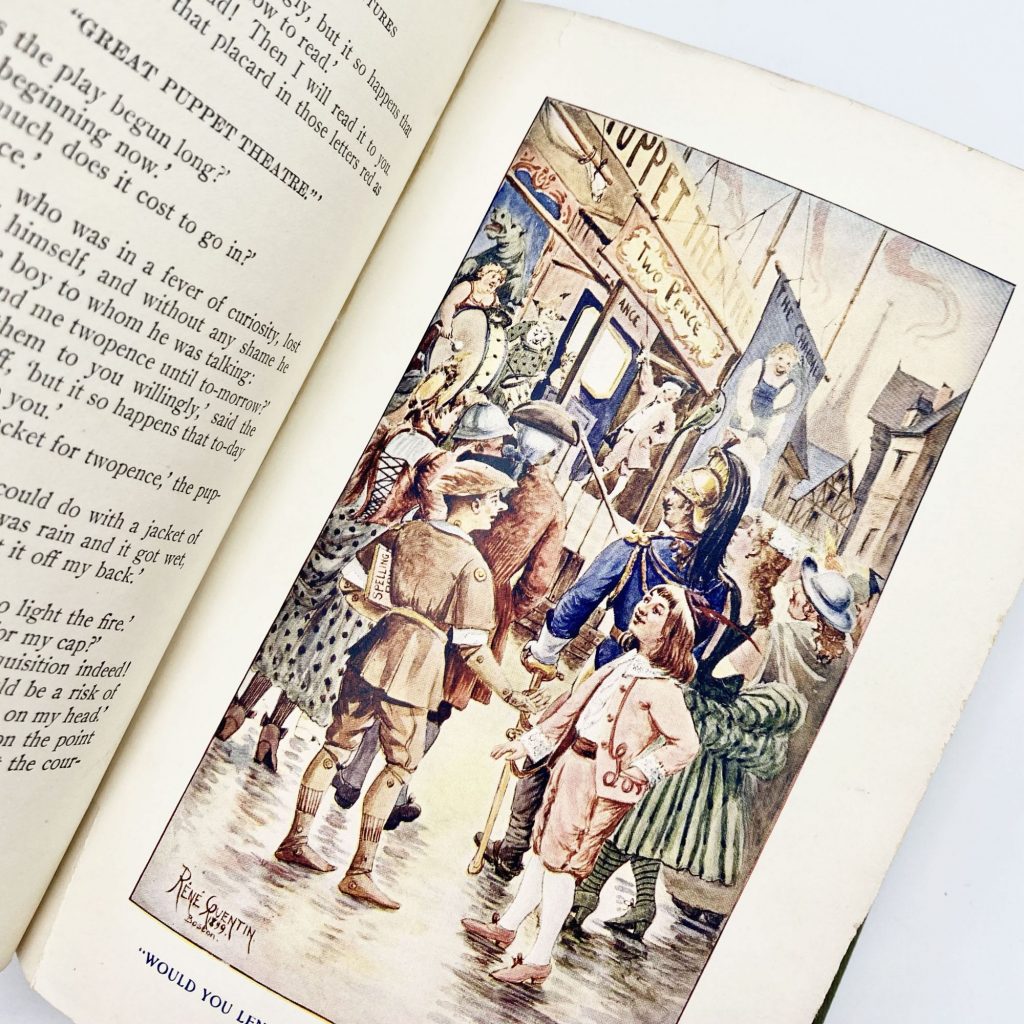

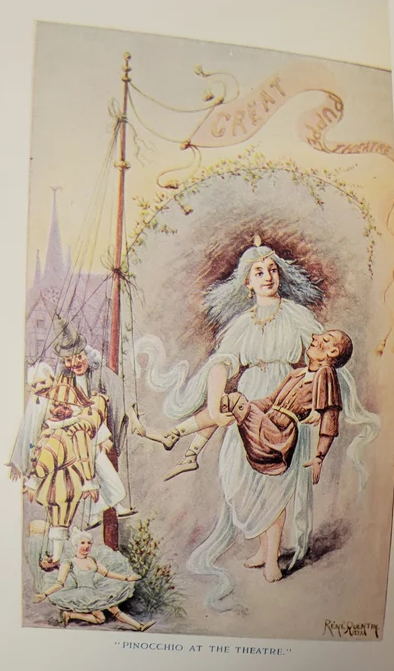

This is an edition by René Quentin (1898). Below some images from it. It goes for anywhere from $150-2000.

L to R (clockwise): Louise Neaujon (1939), Gretta (1930), Charles Folkard (1927), Maud and Miska Petersham (1932). Below find images from Petersham’s edition.

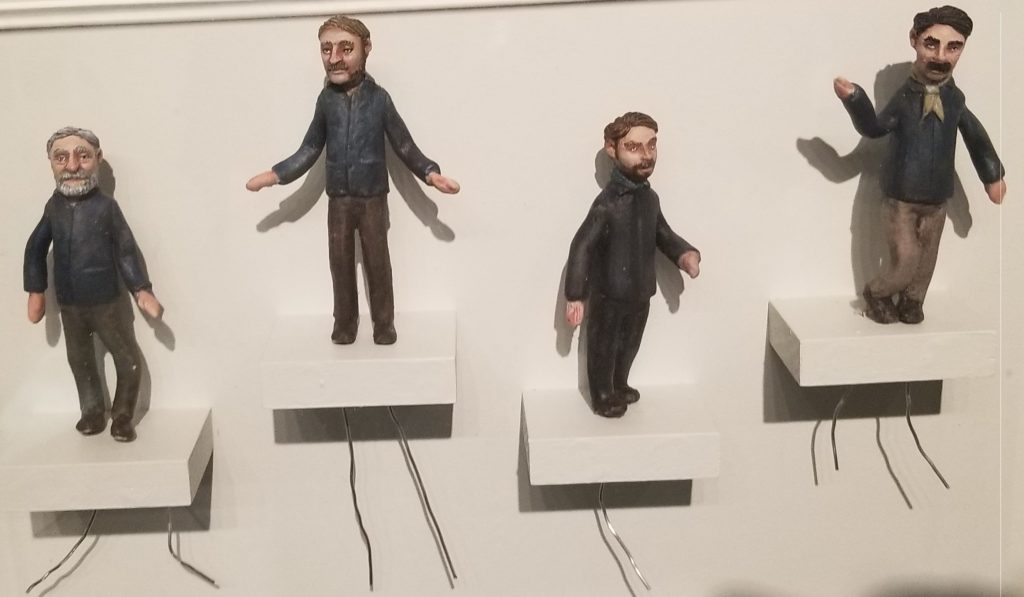

Some additional maquettes/puppets not shown on the main floor.

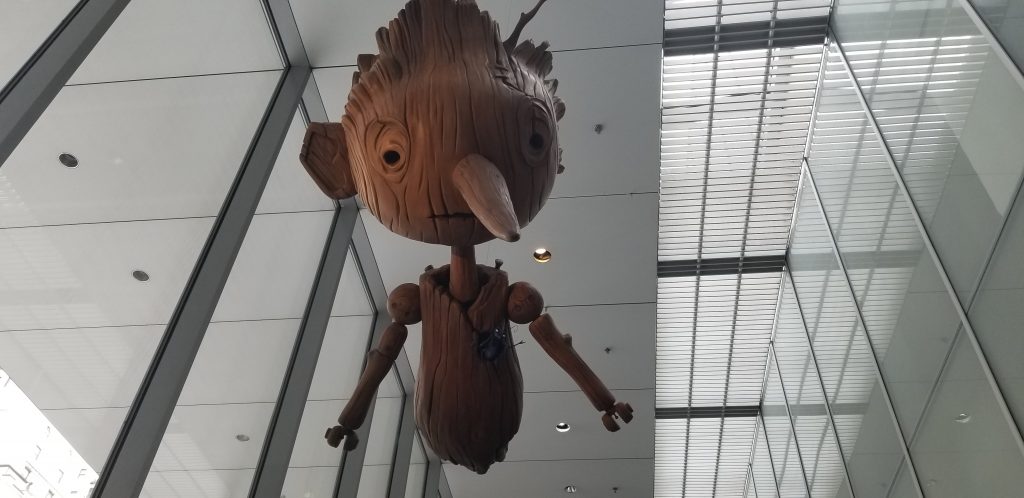

An extra sized Pinocchio sculpt with Jiminy Cricket in his “pocket”

and finally a large print of James Jean’s now sold out Pinocchio art print next to his sold out The Shape of Water print with a Hellboy clip on a large screen.